Gemstones and Lapidary

How Ethical is the Use of Coloured Gemstones in Contemporary Jewellery?

What would you do if I told you that the coloured gemstone that you wear on your neck came from a country where the mining process is connected to serious human-right’s violations and has a detrimental impact on the environment? Would it have stopped you from purchasing it? Would it stop you from wearing it?

We are fortunate enough to live in an age where there is a wealth of information at our fingertips. With almost every household owning tablets and computer’s we can find anything we want to on the internet. It is largely due to the internet that certain sectors have been exposed for unsavoury ethical practices and have had to change their ethical policies. I think that the coloured gemstone industry has a dark history that should be highlighted to people when they purchase these items of beauty. In comparison, the food and fashion industries have increased their transparency because of the demand for knowledge of where our food comes from and how garments are made and significantly, who made them. It could be argued that not enough is being done in the coloured gemstone industry to educate the public on how their gems move from a mine to the marketplace and the process that it goes through before it reaches the consumer.

An article written by, Ali Gray for Elle magazine titled, ‘How Ethical is Your Jewellery’, states that ‘The cachet of owning a gemstone is entirely undermined if it originated from a mine that exploits its workers or damages the environment’.

Many articles on this subject state that consumers are becoming more aware and ‘they are demanding greater transparency from the companies who provide their goods.’ (Article: The Colour of Responsibility: Ethical Issues and Solutions in Coloured Gemstones written by Jennifer Lynn Archuleta For Gems and Gemmology, Summer Issue, 2016).

There is some evidence pertaining to this, but it seems inadequate and there is a lack of disclosure to the consumer because either it does not occur to them to ask or because they don’t know that they should be asking these questions.

To sum up the point, I think that most people would be horrified if they thought for a second that the gemstone that they were about to purchase contributed to the decline of an already endangered species such as Lemurs, or was used to fund the Taliban, or was extracted from a hostile environment by a small child who has been forced into Child Labour. As jewellers, we have a responsibility to make people more aware of what is happening and the severe negative impact that this industry is endorsing.

When I talk to friends and family about what they are doing to help save our planet they usually talk about how they have started to eat less meat or that they are completely vegan. And if they tell me that they are alarmed by modern day farming then I rather enjoy pointing out that the same things happen in the gemstone industry and that if they are willing to stop wearing leather products then I would only be too willing to go through their jewellery boxes and show them which pieces of their jewellery should follow suit. It is the same atrocities with a different product.

So, what questions should people be asking when they purchase a gemstone or a piece of jewellery when the retailer does not willingly provide the information? Jose Luis Fettolini writes in his book ‘Sustainable Jewellery’, that we must consider:

‘Do I really want my jewellery pieces to be linked to the suffering of others?’ And for the person involved in making the piece, ‘Am I aware of the environmental and ethical impact produced by my activity?’

Many of the articles that I have read have talked about the aspect of child labour and the conditions under which these children are working. ‘An estimated one million – and possibly many more – children work globally in artisanal and small-scale mining, in violation of international human rights law, which defines work underground, underwater or with dangerous substances and hazardous and, therefore, among the worst forms of child labour and prohibited for children’.

It is only common sense that the above is forbidden by law in most countries. And yet these laws are being broken and it is not evident that there are attempts being made reinforce to them.

The article goes on to say, ‘Many children work in deep, unstable pits; some have been injured or killed in accidents. Children suffer respiratory disease from inhaling dust, pain and back injury from the lifting of heavy rocks, and other health conditions from mining. In artisanal and small-scale gold mines, children may be exposed to toxic mercury, which is used for processing, and can cause lifelong brain damage and other irreversible conditions.’ (The Hidden Cost of Jewellery: Human Rights in Supply Chains and the Responsibility of Jewelry Companies, written by Jo Becker.)

If this were happening in the UK at present, then I believe that arrests would be made. Yet it is happening globally with the financial support and acknowledgement of well-known and reputable brands. How is this any different to a person donating money to buy arms? These companies are getting a product in return which is even less moral and should be deemed illegal. Their mere knowledge of these occurrences makes them accessories to criminal activities.

There are an estimated 40 million people in this world working in artisanal mines and each of them face these issues, not just children.

There are many impoverished countries that mine gems and precious metals and it is impossible for me to discuss all of them all. In my opinion, Madagascar is home to the worst cases of crimes against humanity and has a total disregard for the environment and so therefore should be a primary source of discussion in this topic.

Madagascar is one of the poorest countries in the world and has a multitude of precious gems buried beneath its surface. According to the magazine article, ‘Dark Crystals: The brutal reality behind a booming wellness craze’ written by Tess McClure for The Guardian, ‘Gems and precious metals were the country’s fastest-growing export in 2017 – up 170% from 2016, to $109m. This island country of 25 million people now stands alongside far larger nations, such as India, Brazil and China, as key producer of crystals for the world. And in a country where infrastructure, capital and labour regulation are all in short supply, it is human bodies rather than machinery that pull crystals from the earth. While a few large mining companies operate in Madagascar, more than 80% of crystals are mined “artisanally” – meaning by small groups and families, without regulation, who are paid rock bottom prices.

These poor people are the ones who put their lives on the line every day with extraordinarily little financial gain and yet manufacturers are making phenomenal profit from their misery and terrible working conditions.

It is apparent that buyers are aware of the situation but choose to ignore the situation. For example, the owner of Madagascar specimen’s, Liva Marc Rahdriaharisoa, who exports 65 tonnes of crystals per year from the country admits that he is aware of the awful conditions from the mines that he buys from. But because he has a stone cutting facility in Madagascar, he outweighs this with the knowledge that he has created steady jobs for people. Whilst that may be partially true, he is still ensuring that the cycle continues. He is fully aware of how much these desperate people get paid as he says, ‘When you see in the rough, (stones weighing) like 50kg, 60kg, they drag it four, five kilometres, two or three per day, and earning only $1’. He then goes on to say, ‘Maybe they (shops in the US) don’t explain it to their customers. It is business for them, they want money. They will never say: “I buy this for $1 and I sell to you for $1,000,”.’ (Dark Crystals: The reality behind a booming wellness craze, written by Tess McClure for The Guardian, September 17th, 2019.)

And so, the sad cycle of exploitation continues. It seems that the whole system is flawed for these unfortunate people. What exactly can they do about it? It seems that the answer is – absolutely nothing. Not without the help of the people who are currently part of the problem.

Mining in Madagascar also poses a clear and present threat to a beautiful and picturesque country. In order to set up new mining sites the rainforest needs to be cut back to make way for excavation. These sites will never be what they once were. These trees will never be replaced once those mines have been depleted.

Not only do these mines threaten the lives of those people who work in them, but they cause serious problems for the wildlife.

Sri Lanka used to be the leading country for sapphire mining but then in 2011 sapphires were discovered in Madagascar. Madagascans descended upon the area of CAZ (Ankeniheny-Zahamena Corridor) in droves and even though it was a protected area, they still uprooted trees and diverted streams all in the hope of finding sapphires. According to an article written for National Geographic by Paul Tullis entitled, ‘How illegal mining is threatening imperilled lemurs, ‘A hundred million dollars’ worth of sapphires and other gems were smuggled out of Madagascar in 1999 alone,’.

This is an incredible number of gems, considering it has all been done under a government who clearly does not have the resources to protect the environment or to safeguard their country against illegal mines and mining practices. Gem mining has been the major cause of the loss of habitat. Tullis points out, ‘Madagascar has the third-highest rate of biodiversity on Earth, after Brazil and Indonesia. Eight of every 10 of its plants and animals are endemic. It has 300 species of reptiles and 300 of amphibians, 99 percent of them found nowhere else. Chameleons 62 species. And along with the nearby Comoro Islands, Madagascar is the only place on the planet that is home to wild lemurs, 113 species in total. These species do not exist elsewhere.

Due to the stricken rainforest, 38 species of lemur are critically endangered and 17 have already become extinct. Gem mining has taken away their homes and in turn their source of food.

If we look back on the history of jewellery, people adorn themselves in pieces to show their prestige or wealth. Not everyone could afford to purchase jewellery in the 1900’s and therefore jewellery could be perceived as the ultimate in luxury. We have now entered a world of mass production where jewellery has become more accessible and the demand is much higher than it used to be. The global empires of the jewellery making industries such as Cartier started with small workshops and humble beginnings. Due to their amazing designs and bold colour combinations Cartier became a leading brand and a household name.

Cartier was renowned for making one off pieces of jewellery for the rich, royalty and the famous using the some of the most celebrated stones in history such as ‘The Hope Diamond’.

As I read the below quote from Alfonso Alfaro, I am encouraged by the Cartier ideal but then we must realise that things have changed now and with greater demand comes a greater risk to artisanal miners and our environment.

“Cartier is part of those companies whose existence proves that not everything in the contemporary world is mechanism and mass consumption, that there is still a space for another way of conceiving relationship between men and objects.”

Cartier auctioned a ring through Sotheby’s in May of 2015 known as the ‘Sunrise Ruby’ which contained a 25.6 carat Burmese ruby. It is now the most high-priced ruby and the most expensive coloured gemstone and the costliest non-diamond gemstone in the world. It fetched a whopping $30,335,698 at auction.

Burmese rubies are shrouded in conflict due to the fact that the monies generated from the mining industry are ‘controlled and distributed to the country’s military, which has been accused of committing horrific atrocities against the country’s Muslim minority – crimes that the United Nations has gone on record to call “a textbook example of ethnic cleansing”. (Article written by Panna Munyal, Is the Burmese ruby the new blood diamond? For, The National, February 4th, 2018).

In 2017 Cartier made the decision to stop purchasing gemstones from Myanmar, Burma, with a statement saying, ‘Cartier strongly believes in the importance of ethically sourced materials, (even though) current international rules permit these gemstone purchases.’

There are people of the mindset that we should ban imports from certain countries because of their unethical practices. And whilst this may be true of military run countries, I feel that this may be the wrong decision for other countries. If we ban the sale of stones from unethical sources, then the miners will make no money at all. It may also mean that this ban will create a black market and therefore put the cost of these gems up even further. It seems to be one of those awful Catch-22 situations where there is no right or wrong answer. With no process in place and no worldwide organisation to maintain the situation then there will be no end to the misery and suffering of these people and the demise of our planet will continue in order to bring gemstones to the world. I think that we as jewellers need to start asking the right questions when we source our gemstones. We need to know which countries they came from so that we can track the history of that countries mining practices.

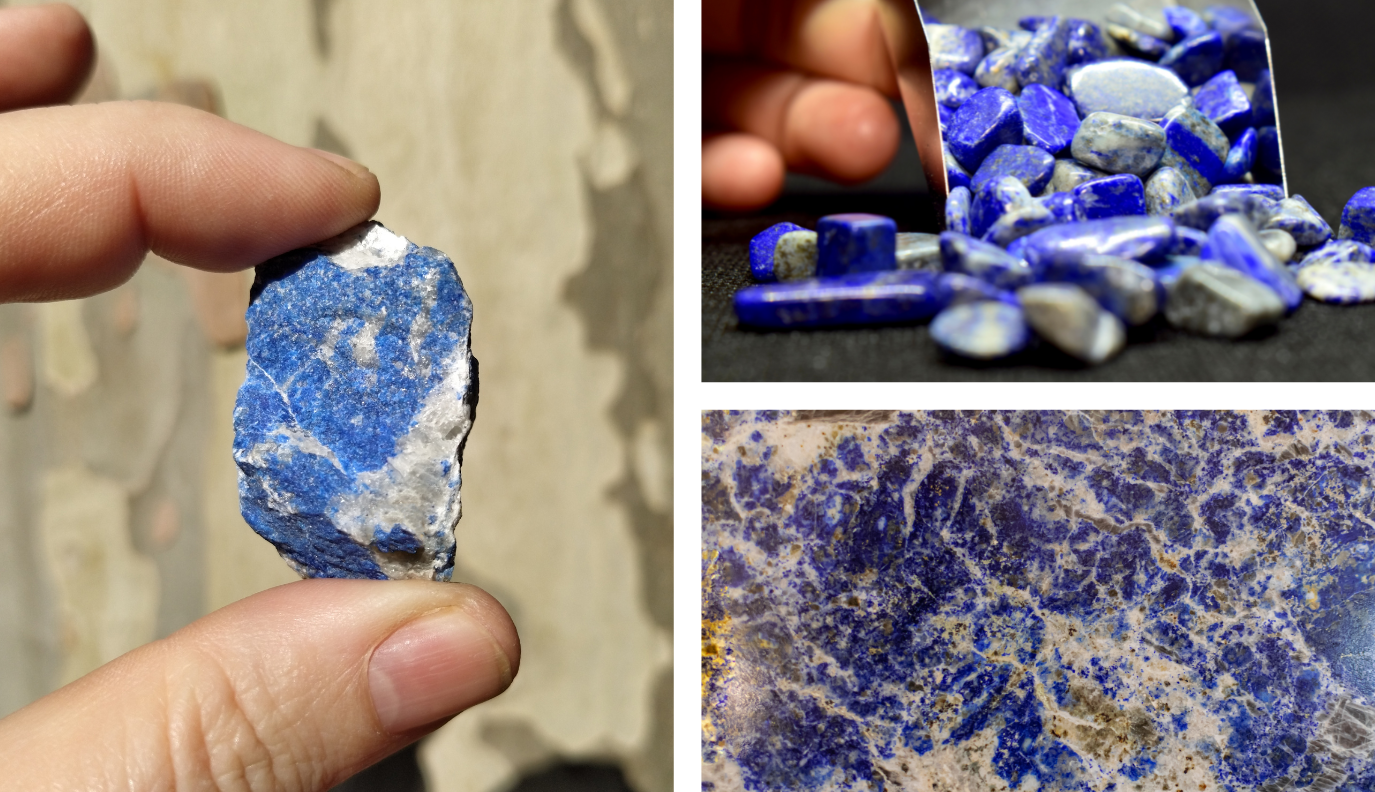

Afghanistan is a major source of Lapis. It can also be found in Russia and Chile and smaller quantities are found in Italy, Mongolia, Canada and USA.

Production of Lapis from the Badakhshan province in Afghanistan ‘raised approximately US12 million for armed groups in 2015, with an estimated US4 millions of lapis mine revenue being paid to the Taliban (Global Witness, 2016). (Article: The Colour of Responsibility: Ethical Issues and Solutions in Coloured Gemstones written by Jennifer Lynn Archuleta For Gems and Gemmology, Summer Issue, 2016). The lapis is mined illegally through illegal contracts and intimidation and as a result the government lost ‘US$18.1 million’ in income in 2014 from just two of their mining districts. By 2016 there were still no efforts being made to control the situation even though the government had acknowledged the issue.

Jose Luis Fettolini writes, ‘Mining, which is linked to the jewellery sector, is a destructive, polluting and cruel industry’.

Ultimately, I am baffled by the content of articles saying that people are becoming more aware of the situation when people who work in the industry seem to be unaware. And if they are aware of the situation then why don’t they talk about it on their web pages or blogs?

As jewellers I think that it is your responsibility to do your own research and find yourselves a trusted source to buy stones from. It is your responsibility to seek ethical suppliers and consider the impact you are making within your business practices.

I have worked in the jewellery business for over 25 years and even though I have always had a passion for gemstones I would say that it has only been in the last 9 or so years that I have started to research where my stones come from and realised with mounting concern that the world is facing a huge issue here.

I source my stones from two suppliers in the world. The first being, Oregon, USA, where I will only purchase from one person because he can tell me everything that I need to know about what I buy. If he did not mine it himself then he knows who did and I trust him implicitly.

The other country that I source from is Sri Lanka. Sri Lankan’s have the most admirable of mining practices, strict laws on areas of mining and have also placed emphasis on teaching Sri Lankan’s to identify and cut gems so that everything can be kept in house. I have spent months travelling through Sri Lanka visiting the mines so that I can check the conditions in which they work. I pick up rough gems and then take them to a local gem cutter. I have also built a close friendship with four local gem dealer’s whom I now consider to be trusted sources. They are all aware that I will only buy Sri Lankan gems from them.

I have found that my customers enjoy being told the story behind where their gemstones came from whether they ask me or not. I tell them the story in the hope that when they procure from someone else, they may think to ask questions as they enjoyed the process that they went through when they purchased something from me. Each piece that I make and every stone that I own has a story behind it and it deserves to be told. It is a story of fun and laughter and friendships and not one of misery, poverty, and death.